The Confederacy's Biggest Blunder

The catastrophic mistake that cost the Confederacy the Western Theater

The Union forces were cut off. General John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, exhausted from their long withdrawal from Columbia, Tennessee, was walking into a trap as they marched ahead in the darkness. Up ahead, John Bell Hood’s 30,000-man-strong Army of the Tennessee was waiting at Spring Hill, like a pair of jaws, ready to clamp down on Schofield’s forces. It was going to be an annihilation.

All afternoon, November 29, 1864, a part of Schofield’s army was engaged up the road at Spring Hill, but the bulk of his forces were well behind the fighting, slogging toward the sound of battle. His units at Spring Hill were outnumbered. All the Confederates had to do was capture the road to Franklin, and Schofield’s retreating forces would slam into the brunt of Hood’s army. Why would the Confederates not take advantage of the open road? If they captured it, Schofield’s men would be trapped. It was a basic, common-sense military maneuver.

The Union Army met with something unexpected.

Exhausted Union forces, some having been up for over 24 hours, were ecstatic when they saw glowing campfires in the darkness, by the Columbia to Franklin Turnpike. They had to be Union campfires. Nobody was firing at them, so nothing else made sense. Desperate to sleep, some men moved to flop down next to the fires when a Union officer hissed at them to halt immediately. “Boys, this is a Rebel camp,” the officer whispered. It was blood-chilling as the Union soldiers gaped at the campfires. Lumps on the ground flickered in the firelight- Confederates.

By some miracle, these first lines of Union forces, retreating from Columbia, moved past the sleeping Rebels. Nobody stirred. The rest of Schofield’s forces, at least 20,000 men, crept along the road. The Confederates were just mere yards away. Why didn’t they take the road? The doorway was wide open. Had the Rebels blocked the turnpike, John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio would have marched headlong into an ambush. Instead, they marched by snoozing soldiers.

By sunup, Schofield’s army was gone, moved beyond Spring Hill and onward to Franklin. Besides a few sporadic skirmishes with Confederate pickets, the Union Army walked away intact. It was an absolute debacle for the Confederates. An incredible opportunity was wasted. The chance to crush the Union army, give Hood his desperately sought victory, and change the tides in the west was gone. Within a week, Hood’s Confederate Army would be decimated after two costly defeats at Franklin and Nashville. The Confederates’ final push to turn the tide was blown.

To really grasp the outcome of Spring Hill, we have to ask: Why did the Confederates waste such a tremendous opportunity? Or, how did they?

During a recent visit to Tennessee, I was blessed (while suffering in the treacherous humidity and sweltering heat) to visit several key Western Theater, Civil War battlefields. I made my way to Stones River, Shiloh, Fort Donelson, Franklin, and Spring Hill to check out these hallowed sites.

During my travels, I churned my way through Wiley Sword’s definitive book on the Spring Hill, Franklin, and Battle of Nashville Campaign titled The Confederacy’s Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, & Nashville, published in 1993. Sword’s book was an excellent, yet heartbreaking and gruesome read. John Bell Hood’s hope to save the Confederacy by taking Nashville in the fall of 1864 led to an absolute slaughter of his forces, essentially ending any chance for the Confederacy to carry on in the west at that point. Sword’s descriptions of combat are not for the faint of heart. Some of the most brutal scenes from the Civil War played out during the campaign.

What fascinated me about this lesser-known campaign (that featured a full-frontal charge that towered over Pickett’s infamous assault at Gettysburg) was the Confederate blunder at the Battle of Spring Hill.

The publicly accessible Spring Hill battlefield site is nothing more than a tiny hilltop overlooking the town. A few signs line a brush-hogged path cut up the side of the hill, where you can climb to get a view of the town below. There isn’t much to see, but the Battle of Spring Hill played a crucial war in deciding the Civil War’s Western Theater.

A Little Background:

John Bell Hood’s plan to drive into Nashville and take out the key Western logistical center for the Union Army was the grand plan to take back the initiative out west. Strings of Confederate defeats in both theaters of the Civil War put the Rebel armies in a tight bind. Hood and other Confederate leaders believed that the capture of Nashville would force Union General William T. Sherman to abandon his “March to the Sea.” In October 1864, Hood set off to cross from Alabama into Tennessee.

Hood drove north, crossing the Duck River outside of Columbia, Tennessee, before flanking around to attack at Spring Hill. From November 24-29, the advance bogged down outside of Columbia, Tennessee, but the rebel forces showed their hand, working their way across the river. The Union defenders at Columbia, under the command of John Schofield and under the overall command of George Thomas, were caught off guard. Neither expected a sizeable Confederate force to move on Nashville, especially in light of Sherman’s move to the sea. But they were wrong. Hood’s crossing was followed by a drive toward Spring Hill, aiming for an eventual foray into Franklin.

On November 29, 1864, at Spring Hill, Tennessee, John Bell Hood’s army had the decisive advantage. They’d had the upper hand when Hood tricked General John Schofield into believing he was going to attack Columbia, Tennessee, delaying Schofield’s withdrawal. Schofield had earlier been ordered to hold Columbia as long as he could, giving Thomas time to accumulate reinforcements where the rest of his army was stationed in Nashville.

John Bell Hood’s Army of the Tennessee flanked around Columbia, moving up the road toward Franklin, where his forces engaged elements of Schofield’s rearmost forces at Spring Hill. Late in the afternoon of November 29, 1864, Confederate forces engaged Union soldiers under the command of generals Emerson Opdycke and John Quincy Lane, who did their best to hold off Confederate Cavalry commanded by Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Hood had the perfect opportunity! He’d moved on Spring Hill while the majority of Schofield’s men were withdrawing from Columbia. From the Rally Hill Pike, just east of the Columbia Pike (where Schofield’s forces retreated), Hood sent a mixed force of several brigades to cut off the Union withdrawal by taking the vital road. The only obstacle was a small Union force under David Stanley’s command to the north. The Columbia pike was there for the taking.

What Went Wrong?

Well, a lot.

1. Hood’s Failures:

When the Confederate Army arrived outside Spring Hill on November 29, Hood had been up since 3 a.m. the previous morning. They were on the tail-end of a 35-day, 200-mile march. The General of the Army of the Tennessee wasn’t in the greatest of health. At the Battle of Gettysburg, on July 2, 1863, Hood took a gruesome wound to his left arm, one that rendered it virtually useless. Just months later, on September 20, 1863, at Chickamauga, a gunshot to his right thigh forced an amputation. His staff strapped him into the saddle, where he would stay until retiring for the night. Exhausted and in pain, Hood was ready to retire early on the night of November 29.

After giving initial orders, Hood spent the afternoon at the Absalom Thompson House, where he relaxed for much of the day. After a night of drinking and feasting, he retired early while his army was still held up, away from the Columbia Pike. Wiley Sword claimed that Hood took a swig of laudanum, which promptly knocked him out for the night. Sword’s accusation lacks proof, but Hood’s past wounds, coupled with being tied to a saddle all day, would be understandably painful enough to require something strong to sleep.

Hood’s distance from the action on November 30, while he took it easy at the Thompson house, kept him away from overseeing the chaos playing out at Spring Hill (more on that in just a moment). Miscommunication among his key generals resulted in a confused, baffling military blunder that resulted in the escape of Schofield’s retreating men.

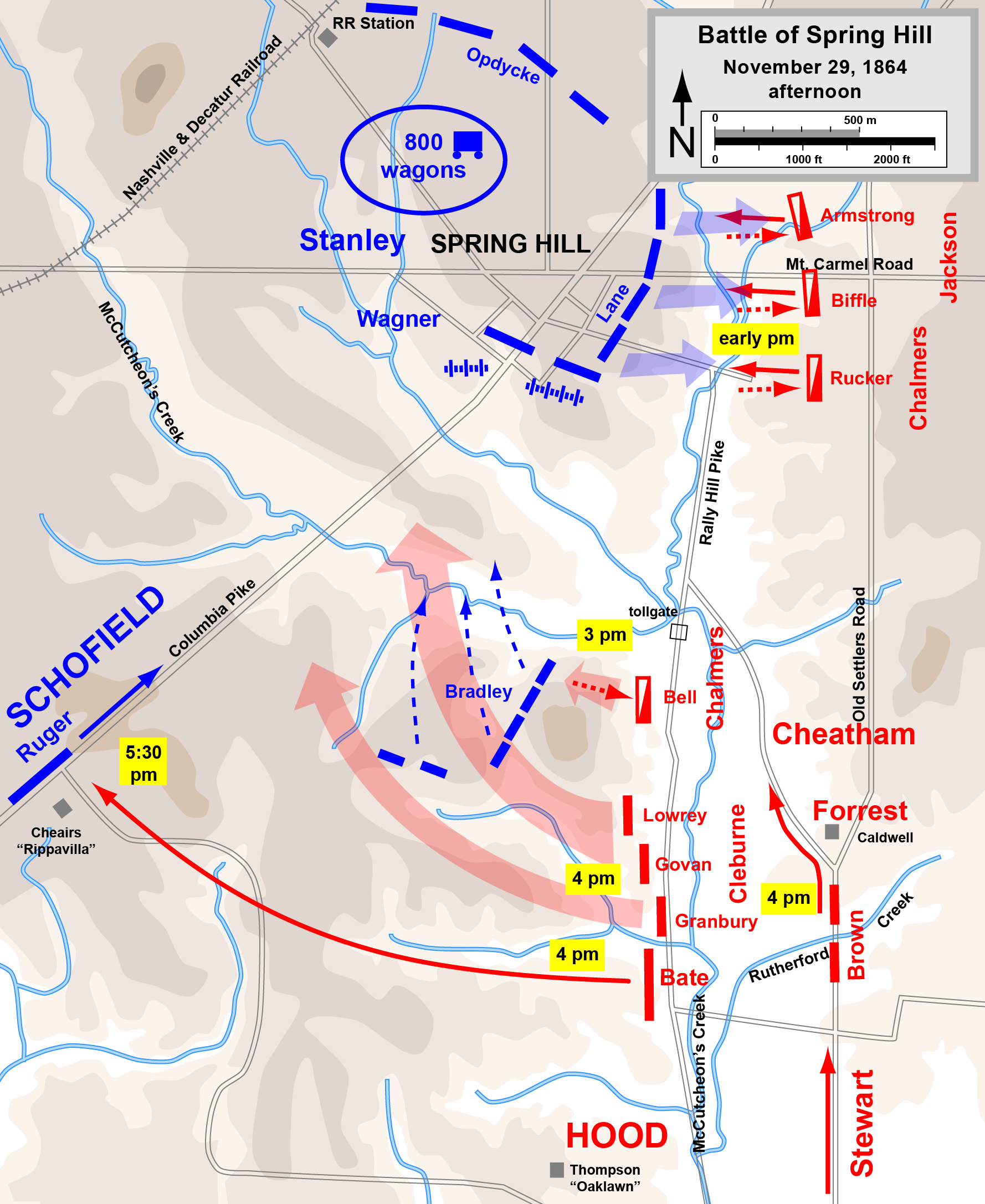

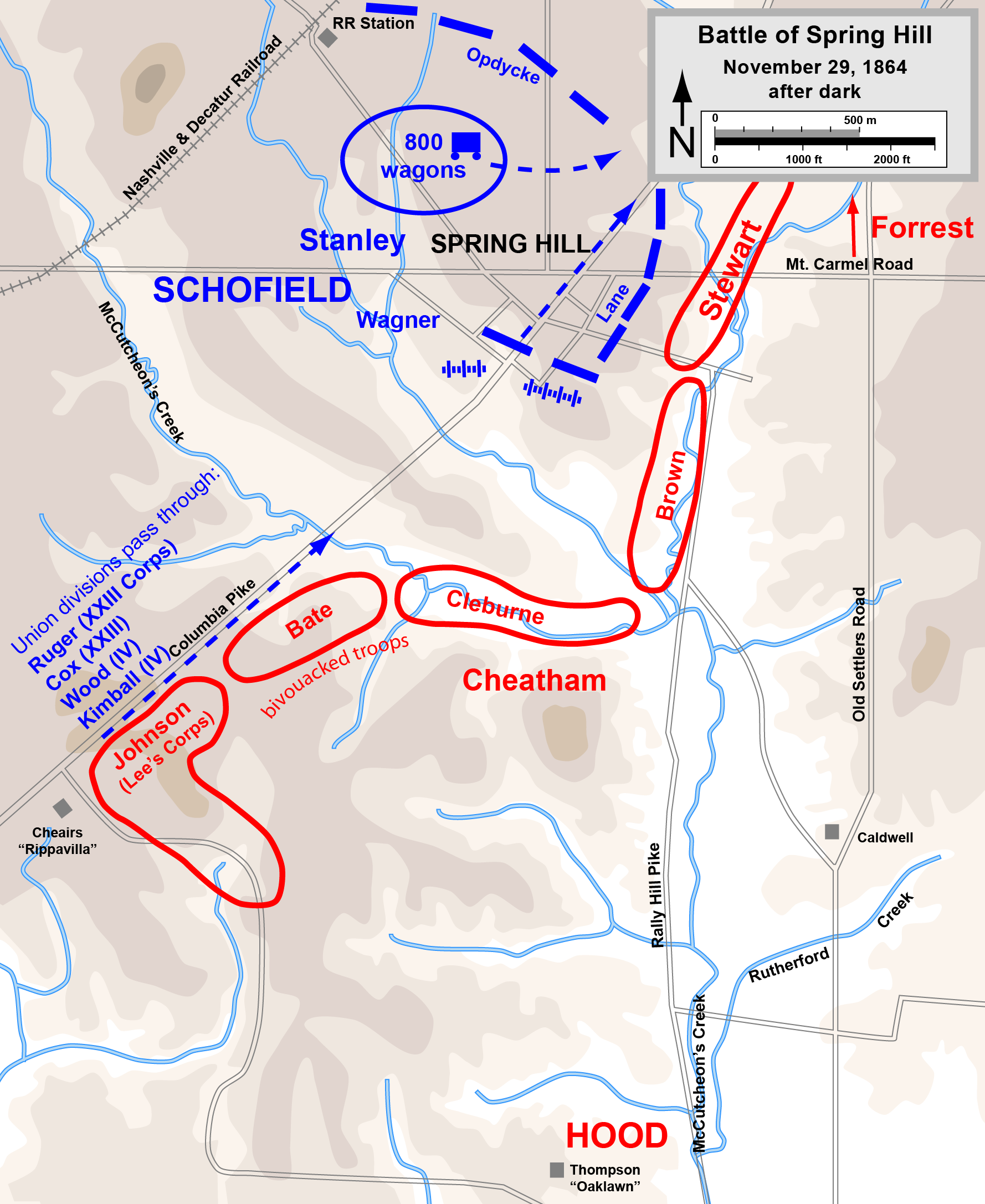

To make this a little easier to follow along here’s a couple of maps, one showing the beginning of the battle, the second is near the end of the day:

Afternoon: Credit: By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9064213

Evening: Credit: By Map by Hal Jespersen, www.posix.com/CW, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9064206

2. Miscommunication:

This is an understatement! To simplify this total breakdown in planning and oversight, I just threw each step into a separate bullet point; otherwise, it’s too many mistakes to track.

As Hood and his army approached Spring Hill, there was still some mystery surrounding the majority of Schofield’s men. Hood first saw the small town of Spring Hill and made that the target. He was riding next to Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, a Corps commander whose mass of men were first on scene. From horseback, Hood pointed over to Spring Hill and ordered Cheatham to take the town.

Cheatham’s men were south of a large battle involving Confederate General Nathan B. Forrest’s Cavalry Corps, which was fighting heavily on the outskirts of town. General Cheatham wheeled around and saw his corps coming up the Rally Hill Pike and passed orders along. They were going to jump off the road that was east of the Columbia Pike and swing up towards the town. Cheatham, with his orders from Hood, spurred off to bring up to direct his men into line. This is where things start to fall apart.

From a higher vantage point, General Hood looked on at the fighting going on around Spring Hill, then looked south, noticing the Columbia Pike was wide open for the taking. While Cheatham was gone, Hood decided to change the plans and rode off to meet General Patrick Cleburne, who was bringing his division on line to march on Spring Hill. Hood now believed the Columbia Pike was more important, so he ordered Cleburne to march to the pike and swing to face Columbia. It would be perfect. They would meet Schofield’s retreating units head-on.

Hood, neglecting to share his new plan with the Cheatham, the corps commander who commanded the men moving into action, ordered a newly arriving division under the command of William Bate to join Cleburne’s left flank and swing to take the pike. Now, the plan has changed considerably, while Cheatham was under the impression that his men were to move north and take Spring Hill.

Midway to taking the Columbia Pike, Cleburne was diverted to assist Confederate soldiers under the command of Lowrey and Govan, who were under heavy flanking fire from Union attackers to the north. Cleburne’s abrupt stop confused Bate, who still thought they were supposed to move on toward the pike, so Bate moved as originally ordered.

Lowrey and Govan’s Divisions were eventually successful in breaking the Union lines held by rookie regiments. The Union fled back towards Spring Hill, but the pursuing Confederates were stopped in their tracks by raking Union artillery fire, stalling the capture of Spring Hill.

At this point, a frustrated General Cheatham, who was still under the impression that Spring Hill was the objective, grabbed an incoming division under the command of General John C. Brown and placed them on Cleburne’s right flank with orders to attack the town. Orders were passed down: as soon as Cleburne heard gunfire from Brown’s men, they were to move up and support the attack.

Cheatham noticed there weren’t any supporting units on Cleburne’s left flank. It’s because that flank, under the command of William Bate, was still under the impression that their original order to take the Columbia Pike was in effect, yet Cheatham had no idea that order was even issued. He rode off to find this lost division, leaving Brown and Cleburne without their commander before a major assault was supposed to kick off.

Cleburne’s men sat around, waiting for Brown’s attack to kick off, but they didn’t hear any guns.

Brown, when ready to attack, bumped into Confederate General Otto Stahl, who flagged him down. Stahl, breathless, rode up and told Brown he needed to call off the attack! Just over the ridge, there was a whole line of Union infantry waiting for him. Brown had his orders, but didn’t want his men slaughtered, so, reluctantly, he decided to wait for Cheatham, who was off looking for Bate’s lost division.

Bate’s Division reached the pike at dark. Their day was spent wandering around in the wilderness, trying to find their way, but there, beyond the trees, they saw the pike! A group of Confederate sharpshooters scouted ahead and engaged a small force of Union soldiers. The popping of rifle fire signaled to Cheatham where the lost division was! Cheatham’s staff officers rode ahead and ordered Bate back to support Cleburne’s left, abandoning the pike!

Further north, a newly arrived corps under the command of Alexander Stewart moved into line on Brown’s right flank. He could see the pike ahead and take it, but he was told to wait and aid Brown in the attack that never came. Frustrated, but with his men exhausted, Stewart ordered his men to bivouac until he could get new orders. The exhausted Confederates gladly collapsed in exhaustion.

Cheatham, receiving mixed signals from finding Bate with orders to take the pike, left his forces to find Hood, who was ready to sleep after a long day. All along the line, the Confederates decided to await clarification of their orders. For many, they could see the empty road ahead, but sleep was too tempting.

A frustrated General Stewart finally found Hood, but it was too late. Hood was shaken awake and, while groggy, met with the confused corps commander. Stewart relayed to Hood that his men were now lying down to sleep for the night. The dazed and groggy Hood sleepily told Stewart to hold off for the night; they would find the Union army in the morning.

You can see where just one key moment before the assault on Spring Hill ruined the entire campaign. Hood and Cheatham’s failure to agree on a plan was detrimental. By the time the Confederate Army could have taken the pike, they were tired, and the darkness clouded their ability to fulfill their orders. That night, Schofield’s men made it past the sleeping Confederates. In the morning, Hood was irate, but still believed he had the initiative, and on November 30, 1864, he ordered his army to move onto Franklin in what would be one of the most horrific and devastating battles of the war, where Hood’s fighting force was effectively destroyed.

Wiley Sword placed the blame at Spring Hill and later at Franklin at the feet of John Bell Hood. Hood certainly deserves his share of the blame, but it might be an oversimplification to put it directly on him.

This argument reminds me of one I had with a reenactor a few years back. They were a group of Union soldiers portraying men on the Rappahannock during the winter of 1862, after the Union had their teeth kicked in at Fredericksburg. I remarked, “Poor Burnside, he never wanted the job.” This reenactor said, “It was his fault!”

I thought about that for a while. Blaming defeats on an overall commander seems to be something common in military history. Poor planning for Burnside was actually an overcomplication of design. His plan at Fredericksburg was ambitious and showed promise from someone who was clearly tactically-minded and professional. The problem with complicated military operations is the excess of moving parts. There’s a lot of blame to go around.

For Hood, this logic plays true. His miscommunication at Spring Hill is unforgivable, but with a large body of experienced soldiers at that stage of the war, nobody thought, “Let’s take the road!” Without orders? Stewart’s men slumped down next to the thing. Brown wasn’t about to make the choice to take the road without orders. There was no doubt that the wealth of military experience in the field should have informed these officers that taking the road was crucial to cut off the Union.

General John C. Brown was an entity that was common during the Civil War: A political officer. His brother had been the governor of Tennessee and connected to the politics of the war; Brown was nervous about any mistakes because of the heat he’d get from throughout the Confederacy. Waiting for orders was the “safe” thing to do. He wasn’t going to rock the boat. After all, he’d survived the political infighting surrounding the replacement of Braxton Bragg with John Hood.

This political pressure embodies the Civil War. On both sides, politics directed so much of the war in a democracy like the United States (and the C.S.A.) Military disasters, losses, or inefficiency had a political cost, so political pressure drove many of the Civil War’s biggest defeats. Hood was just another general under pressure from his political bosses, who pressured him to make his move, or they’d find someone else. So Hood, the fighting general who was known for tenacity and bravery, less so for analyzing a battlefield and showing caution, led his men to a disastrous defeat that effectively ended the war in the west.

In the disaster at Spring Hill, Hood is to blame, but so are his generals. Inaction across the field, when there were few obstacles in the way, is something that should have been more alarming to these veterans. At that point in the war, Hood’s officers and his men would have been hardened battle veterans with enough experience to drive their move onto the Columbia Pike.